In the previous seasons, I had been teamed up with an Australian geologist, Mike Randall, to do geological survey and well-site geology on the Barkly Tableland from east of Tennant Creek to the Queensland border, and we had flown to Brisbane to pick the vehicles and camp equipment. We then drove out northwest for a week or so across the dirt roads of the black soil country via Towoomba, Mitchell and Charleville, then north to Blackall and Barcaldine, then through sheep country west and northwest to Longreach and Winton, then into the semi-desert, red sand, rocky hill and gravel country which led to the mining towns of Cloncurry and Mount Isa – ‘the Curry’ and ‘the Isa’. Northwest again led us to Camooweal and into the Territory along the bitumen of the Barkly Highway and onto the Mitchell grass country and cattle station land of the Tableland.

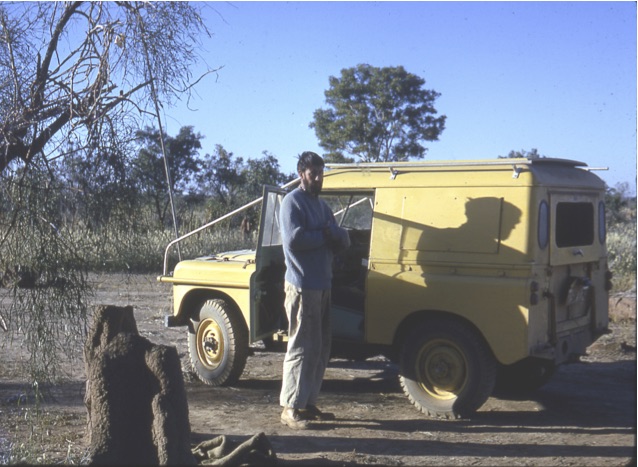

This time however, I teamed up with Ted Milligan, a very astute Kiwi geologist with long field season and well-site experience in the south Tableland and Sandover River area. We’d met up several times out bush and of course in between field seasons back at the Bureau of Miserable Discourses (as he called it!) in Canberra. We got on well together and thought pretty much alike about geology and the principles of mapping.

The ‘trip’ to the Tanami started off ideally. We flew to Adelaide in a DC9, at the tail end of which was a small semi-circular lounge area to which we immediately repaired for a lunch-time coffee chased with a vodka and lime (ship’s lime if they had it).

We transferred to ‘the Alice’ plane in Adelaide and flew north over the endless red desert and dune country to land at Alice Springs and meet Don Woolley, the Bureau’s Resident Geologist there. We picked up our Bedford 3 ton truck and the Landrovers and drove north along the bitumen via Tea Tree Well, the Devil’s Marbles (enormous dark red, rounded and exfoliated residual granite ‘boulders’) and Barrow Creek to Tennant Creek under clear blue skies and warm ‘winter’ sunshine. We had to have a rest period (and a ‘wet’ to get the local news) in the pubs in these places and then we hit the road again, using the fixed throttle to sit on 50mph for the rest of the 300 miles, which made driving a little easier on the right leg! It was dominantly red country under cloudless blue skies, with the few hill ranges and isolated outcrops, scattered stands of gum trees, mulga and spinifex to break up the flat terrain.

The rocky hill country around Tennant Creek soon

came up on the horizon and we stopped in Tennant briefly to meet up

with John Barklay, the BMR’s Resident Geologist, who had just found a

new and better town water supply by mapping the partly buried gravels

of an old water course.

We then set off west into the Tanami - and the Wiso Basin as it was geologically called – along a short stretch of bitumen to set up base camp soon after hitting a bit of a red dirt road seemingly heading off into the back of beyond.

This was quite an experience for me, as this time there were no cattle stations and no regular dirt track northwest to Hooker Creek 200 miles away, and we only had empty 4-mile base maps and copies of the air photos to guide us, and on which to plot our geology!

The first thing I noticed was that the weather had broken! We drove west at sundown but now under a blue sky with high white bands of cirrus cloud disappearing to a vanishing point way down on the horizon ahead of us.

Ted and I followed the road out past Orlando mine to start with and then the tracks of an earlier survey team from the Deptartment of the Interior in 1964, and rolled our swags out on the lee side of the Landrover wheels when we hit the red sand and spinifex of the desert. From the end of the dirt road we were able to follow tyre tracks, slightly sunk into the red sand and sometimes bending around softer claypan patches or low gravel mounds. If the gravel areas were large, you couldn’t always see the tracks and you either followed their general direction or circled around them ‘til you picked them up again. If you hit a gravel patch near sundown you could sometimes see the faint impression or slight shadow difference of the compressed gravel in the low-angled sunlight. These tracks led us onto the Green Swamp 4-mile sheet, our first mapping and drilling area (a 4-mile sheet was 1.5° longitude E-W by 1° latitude N-S), c. 7000sq. miles in old money!

For the next few days we did a recce of the track ahead heading west and west-northwest.

The landscape was dominated by the red colour of the sand and the brown colour of the low hills with loose rock cappings, but scattered dark green mulga and acacia bushes, clumps of green, light tipped spinifex and the odd broken lines of green and white of gum trees stretched beyond as far as the eye could see, making it seem less desert like. The low hills of loose outcrop relieved the initial monotony, and we named one of them Mt. Turnout (‘turnout’ being the word we used for something or someone whose name we couldn’t immediately remember), because none of them had names.

Here too, I experienced the great sense of space again that you get out-bush because your horizons are everywhere only just above the horizontal - no confining hills, mountains or woodland, or city street canyons. We drove across or round white clay pans and dry stream courses which crossed our track, for instance, a seemingly un-named course, running from SSW to NNE across our track, coming from the western part of the Point Wakefield area to our south and on through the Winnecke Tableland to the South Lake Woods area north of us. This may be an extension of the Hanson River which seems to run in from the SE of Green Swamp Well.

We returned eastwards and chose the first drill site (Green Swamp Well #1), set up camp and waited for the arrival of Ginty Gorey and his caravan and his Failing 1000 (good name!) air-rotary jack-knife rig on the back of an International truck. There was also an Ingersol Rand compressor to pump the air around and blow the rock fragments plus or minus any formation fluids (groundwater in our case) out of the ground and which fell around the well head casing.

I had worked with Ginty before, out on the Tableland in 1962, a very hospitable guy with lots of drilling experience, who said he couldn’t read or write and so always wondered why the BMR gave him such small, almost one-word drilling logs to fill in, when all the geologists he’d met used such a hell of a lot of words, frequently including ‘maybe’, ‘could be’ and’ possibly! His rig was also vastly different from the big Sides 90ft rig I had worked with which had big Gardner Denver mud-pump engines and which was used for drilling the deep stratigraphic bore holes on the Tableland and Sandover River in ’63 and ’64.

…And this was when I had my first real experience

of flies. In contrast to the hundreds in the Barkly and Sandover areas,

here there were thousands of them, hour in hour out, every minute of

the day, day in-day out, from sun-up to sun-down. I’d grown a beard to

keep them off my face but the backs of my ears got raw from my constant

flicking the backs of them to get rid of the bastards. I tried a mozzie

net but found it too stifling and awkward every time I wanted to use

the hand lens. In the end, I made up a swaggy’s hat and it worked the

best, not completely, but the best.

When Ginty reached the first drill-site, he jacked up the rig, laid out the pipe and fired up the compressor to check for a start at sun-up.

However, our drilling days started at about 5am when we were woken up by a series of wracking, hacking coughs from Ginty’s caravan, his early morning throat clearing which only stopped with his first cigarette.

In the cool of the early morning before the flies got up, we rolled out from our swags in the lee of the Landrover wheels, ‘parked’ across the breeze direction and lit a fire to get the tea billy going. I had made sure I’d got some stores of powdered milk and Kellog’s Corn Flakes (‘rat tucker’ or ‘chaff’ according to Ted) while he had corned beef or bread and cheese.

After spudding in with the hole-opening bit and sinking the riser pipe, Ginty would change to the next smaller rotary hammer bit and I would spend the day watching the drilling speed for changes and the falling cuttings for colour change. I would periodically pick up a handful of cuttings to examine them with the hand lens while Ginty would control the drilling speed and mark off the depth. I would also bag and label a cutting sample at every 10 feet and at any rock type or colour change. I would examine them, record the depth and write up a description in a drilling log book. At selected intervals we also pulled out the ‘string’ and put on a core barrel to get a good 2” diameter core of between 4-10ft of solid rock for more detailed examination especially for fossils.

The days followed this pattern for each bore-hole, under clear blue skies, light breezes and after the cool early morning temperatures, in up to 70F temperatures.

When we had penetrated the sedimentary sequence and

reached our target depth or an igneous/metamorphic rock (regarded as

basement) at an unforseen, shallower depth, Ginty would pull out the

string, breaking each joint, stack the pipe on the flat bed and cap the

bore. We would move off west to the next site, an unusual-looking,

modern wagon train!

We occasionally struck water and then the compressor would blow the cuttings out in a shower of spray. The depth was noted, a sample was collected, labelled, and stored in a plastic bottle. I learned to be even more cautious when on one occasion, a mottled, light green snake fortunately wriggled away from me as I bent to collect a sample from the pool by the well-head casing.

Ted in the meantime would either drive off to do the ground survey or later take off to do the helicopter survey, prior to which we had always had a previous night planning briefing, confirming the general flight path, direction/destination and the ETR.

We did our mapping by helicopter, a Bell 47G with the pilot following our directions from our reading of the air photographs. For example, during my period of survey, we would plan our traverse, go over it with the pilot and then with a pile of air photos stacked in sequence on my knees, we would take off vertically up to c.300 ft., circle once or twice to work out which photo grey patch we were above - and whether the pattern of patches was still the same as when they were first photographed 20 years earlier by the RAAF. (They were often a bit different because the water courses had changed in the ‘wets’ of the intervening years and the odd spinifex-mulga fires had left burn patches instead of the vegetation patches). Then we would head off to the first promising-looking outcrop.

We each followed the same method of mapping which was new to me but straight forward and logical. I sat alongside the pilot with the stack of air-photos on my knee in the order of our planned traverse. The others were stacked in order alongside me in a canvas knapsack. The day consisted of taking off, landing, examining, recording and taking off again to and from any rock outcrop or interesting exposure (of gravel!), or to and from any unusual pattern on the photo to check its nature.

Apart from a hammer and a lens, I was also armed with a compass point (mathematical type) a pencil and a field note-book, and the routine was to land, examine the rocks for as long as necessary, pierce the photo with the compass point at the site, ring the point with the pencil, give it a pre-selected site number, and under the same number, write a description in the note-book. This was really efficient (and maybe a refinement would have been to tape record a description) and we covered a lot of ‘ground’. At times the noise would get to me as the motor was just behind us, and the yo-yoing up and down only rarely made me feel queasy but never caused us to stop. We only stopped to refuel where 44 gallon drums of Avgas had been dropped off by truck at pre-determined refuelling sites. Tasted worse than petrol if you got the siphoning wrong!

We also flew over the vast ‘fossil’ dune country to the south west around Lander River, spectacular empty land of red sand, widely spaced dunes anchored by scattered spinifex and mulga. We didn’t land as no rock outcrops were visible, so I marked the air photos to confirm the landscape and the pattern. I was lucky enough to see a rare sight after the rain, when we found several small billabongs left along a usually dry river course, not a frequent occurrence out here,

Evening meals were often shared with Ginty and his partner whom, we were told, had been left by her man at the Mica Mine on the Plenty River in the Harts range east of the Highway. She and Ginty had taken up together and she was pregnant now and Ginty was looking a bit more family bound! She was very kind and a bit upset when she heard I was married and had left my wife in Canberra; she gave me a small glass tube full of pieces of opal as a present to take back to Christine (several of which she set in silver cuff-links for me which I wear in this day and age). Ginty’s instruction to ‘help yourself’ meant just that! As I sat there, being politely English, I was told to serve myself, ‘as you don’t invite somebody in to eat and then dole out how much they should have’.

One day near the old Whitlock track, we found an old Mitchell bomber, bright silver as if sand scoured and minus an engine. We messed about and took a few photos, with Ted saying that it was out of Darwin and had force-landed near the end of the Japanese fighting, and he’d heard that the missing port engine was running the cooling system for the beer in the Tennant Creek pub on the east side of the highway!

We only went into the Creek once for some supplies

and though we hadn’t met any aborigines out in the desert, we met some

in the bar (in the pub on the west side of the highway). We were having

a yarn at the bar and it was here that one of them came up to me and

asked me if I was a ‘Jesus man’. I shook my head a bit puzzled and

asked why, and he grinned and pointed at my beard; he thought I was one

of the Mission men!

We spudded in at Green Swamp Well #1, 54 miles west of Tennant on 9th June ’65 and spent the rest of the month drilling the four holes under my care. Drilling time varied from 2–6 days and travel distances between the holes varied from 15 -30 miles, normally a day’s travel so you can see that the surface was relatively firm and made for easy going. However, between 17–21st June, between GSW #3 and #4, our 15 miles took us four days!

This was because we had rain! The clouds built up from the NNW and the lightning displays were spectacular, thunder rolls heralded the start of the rain and it rained for several hours overnight. We had capped off #3 and set off west making the usual steady speed over the hard packed sand until without warning we hit a soft patch and the big rig started to sink, settling eventually at just below its tray. Ginty tried reversing, but it was no good. The other vehicles had stopped further back when they saw what was happening and were safe, and didn’t try to drive around. Towing backwards didn’t work, and neither did digging a shallow ramp up and out to go forwards. Trying to get traction only caused further sinking. Nice place for a well! So we settled down to wait, did some servicing of the gear and watched the amazing sight of the desert bursting into bloom. All around us the red sand became a carpet of coloured flowers which lasted for about a week. We just had to wait for the water to drain away and evaporate from underneath and around our track as we’d obviously hit a silt or clay pan which had become waterlogged overnight. Three days later when the area around the ramp had dried out we put mulga branches and matting down and slowly inched our way out, being winched by the truck which had found a hard route around to ahead of us.

The only other thing of note that happened during my time out there was being left in charge for a few days while Ted went into hospital in the Alice. He said one morning that he’d had grumbling appendix for a while and thought that he should have it out as could be a longish field season ahead for him. It was good to have him trust me and we kept in radio contact at regular intervals each day he was along the track.

However, when Ken Smith heard of it back in Canberra he got a bit upset and just had to leave his desk and fly out with Fred to come and supervise. Ted was right about his condition; it was sorted within three days and he was back up the Highway without there being any problems for him – or me. No worries as they say!

He then took over doing the well-site geology with Ken in July but wasn’t too happy about it, and after doing some helicopter survey, flew back to Canberra to get stuck into the thin slide preparation, examination and to write up the rock sample descriptions.

Besides, the weather had broken again!

Converted from .doc by David Nash, 30 August 2021